Saturno in Foro

Il tempio di Saturno fu eretto nelle vicinanze di un’antica ara ad un angolo del Foro ai piedi del Campidoglio [in faucibus (Capitolii) Var. L. L. V, 42; in Foro Romano Liv. XLI, 21, 12; ad Forum Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1; in imo clivo Capitolino Fest. 322; Serv. Aen. VIII, 319; sub clivo Capitolino Auct. Orig. III, 6; ante clivum Capitolinum Serv. Aen. II, 116, Hygin. Fab. 261; Dion. H. I, 34, 4; VI, 1, 4]. Era il tempio più antico di cui fosse ricordata l’edificazione negli archivi dei pontefici; una tradizione ascrive la sua costruzione a Tullo Ostilio, mentre secondo un’altra fu iniziata dall’ultimo Tarquinio [Var. apud Macr. I, 8, 1; Dion. H. VI, 1, 4] e poi dedicato all’inizio della Repubblica da Titus Larcius, dittatore nel 500 aev [Macr. cit.], o da Aulus Sempronius e M. Mamercus, consoli nel 497 aev. [Liv. II, 21; Dion. H. Cit.], o da Postumo Cominius, console nel 501 e 493 aev. [Dion. H. Cit.]; un’altra versione vuole che sia stato lo stesso Titus Larcius ad iniziarne l’edificazione durante il suo secondo consolato nel 498 aev. [Dion. H. VI, 1, 4]. Una tradizione differente, trasmessa da Gellio, la attribuisce a L. Furio, tribuno militare, in esecuzione di un decreto del Senato [Gel. apud Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1]. In ogni caso il tempio può essere fatto risalire sicuramente all’inizio del periodo repubblicano. Nel 174 aev fu costruito un portico lungo il crinale del Campidoglio, dal tempio di Saturno, fino alla cima del colle [Liv. XLI, 27, 7]. Nel 42 aev fu ricostruito da L. Munatius Plancus [Suet. Aug. 29; CIL VI, 1316; X, 6087]. Nel IV sec fu danneggiato da un incendio e restaurato per voto del Senato [CIL VI, 937]. La data della dedica era il 17° Dec. ai Saturnalia [Fast. Amit. ad XVI Kal. Jan., CIL I2, 245; 337; Liv. XXII, 1, 19].

Durante la Repubblica il tempio ospitava il tesoro dello Stato, l’aerarium populi Romani o Saturni, a cui erano preposti i quaestors [Fest. 2; Solin. I, 12; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 3; Plut. Tib. Grac. X; App. B.C. I, 31]; per questo vi si trovava una bilancia che un tempo era usata per i pagamenti e che rimase come simbolo di questa funzione [Var. L. L. V, 183]. Durante l’Impero mantenne questa funzione, ma l’aerarium Saturni era solo la parte dei fondi pubblici sotto il controllo del Senato, distinto dal fiscus dell’imperatore, amministrata da praefecti, anzichè quaestores [Plin. Ep. X, 3, 1; Thes. ling. Lat. I, 1055 – 1058]. Gli uffici dei funzionari pubblici si trovavano probabilmente al di fuori, nell’area saturni fino alla costruzione del Tabularium nel 78 aev. in cui furono trasferiti gli archivi. Altri documenti pubblici erano affissi alle pareti del tempio e alle sue colonne [Cass. Dio XLV, 17, 3; CIL Ia, 587, col. 2, 1, 40; Var. L. L. V, 42).

Nel timpano si trovavano statue di Tritoni e cavalli [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 4], e nella cella si trovava una statua di Saturnus che veniva unta di olio e avvolta in panni di lana [Plin. Nat. Hist. XV, 32; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 5; Rosch. IV, 431] e portata nelle processioni solenni [Dion. H. VII, 72, 13].

Saturnalia

I Saturnalia erano la festività dedicata a Saturnus. In origine duravano un solo giorno, ma l’uso popolare prolungò i festeggiamenti fino a sette giorni [Macr. Sat. I, 10, 1 – 5; 18 – 24; Cic. ad Att. XIII, 52], così da comprendere gli Opalia e i Larentalia. Questa dilatazione fu probabilmente favorita, all’inizio, dall’identificazione di Saturnus e Ops con Kronos e Rhea e quindi con la volontà di unire le festività dedicate a queste due divinità. Augusto limitò i festeggiamenti a soli tre giorni, che furono successivamente aumentati a cinque [CIL I, 337] e, più tardi, di nuovo a sette; tuttavia solo i giorni in cui cadevano festività religiose erano festi [Macr. Sat. I, 10, 24].

Un’ampia digressione sulle possibili origini di questa festa si trova nei Saturnalia di Macrobio [Macr. Sat. I, 7]. In un’epoca estremamente antica sul Lazio regnava Janus, assieme alla sposa Camesis; la loro capitale si trovava sul monte Janiculus. Saturnus, arrivato in questa terra a bordo di una nave, vi si stabilì ed inaugurò la pratica dell’agricoltura (gli fu attribuito l’epiteto di Stercutus perchè fu il primo a concimare i campi), della coltivazione degli alberi da frutto, dell’innesto e della lavorazione dei cibi, per questo la sua statua tiene in mano una falce; edificò la propria città, Saturnia, sul monte che anticamente era chiamato Saturnius e poi Campidoglio [Var. L. L. V, 42; Dion. H. I, 34; Fest. 322; Solin. I, 13; Serv. Aen. II, 115; Verg. Aen. VIII, 321]. Proprio in onore dell’arrivo di Saturnus, le prime monete romane portavano la prora di una nave e l’effige del Dio. Dopo un lungo regno Saturnus sparì e Janus gli tributò un culto, edificando un altare (ara saturni o fanum saturni in faucibus, ai piedi del Campidoglio [Var. L. L. V, 42; Dion. H. I, 34]) ed indisse i primi Saturnalia. Il regno di Saturnus fu un’età dell’oro: non vi era distinzione tra schiavi e uomini liberi e vi era abbondanza di cibo e ricchezza. Il suo culto sarebbe poi stato portato avanti dai compagni che Ercole lasciò in Italia durante il suo passaggio e che si stabilirono sul monte Saturnius [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 18 – 27].

Un’altra versione fa risalire l’origine del culto di Saturnus ai Pelasgi, l’oracolo di Dodona prescrisse loro, una volta giunti al lago di Cotila e sconfitti gli Aborigeni, di consacrare la decima del bottino ad Apollo, di sacrificare delle teste ad Ades e degli uomini a Saturnus – Kronos. Essi seguirono le istruzioni ricevute e, una volta stabilitisi in Italia, costruirono un tempio per Ades ed un altare per Saturnus, dove compirono i sacrifici prescritti; indirono anche le prime feste in onore di Saturnus [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28 – 31]. Quando Ercole arrivò in Italia, pose fine ai sacrifici umani e ne convinse gli abitanti ad offrire ad Ades dei simulacri a forma di teste (oscilla) e a Saturnus dei ceri accesi anzichè esseri umani [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 31 – 32]. Entrambe queste versioni fanno risalire il culto di Saturnus ad un periodo molto anteriore alla fondazione di Roma.

In un’ulteriore versione la fondazione dei Saturnalia sarebbe stata concomitante alla dedica del tempio di Saturnus, compiuta da Tullo Ostilio, o da Tarquinio il Superbo o dal tribuno militare L. Furio, per ordine del Senato [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1].

I Saturnalia, assieme a Divalia e Larentalia, si inseriscono in un sistema di festività dedicate a divinità ctonie (essendo Saturnus ritenuto Dio ctonio [Plut. Q. R. 11; 34] o infero [Mart. Cap. I, 58] e non celeste) poste alla fine dell’antico calendario romano, che, probabilmente formavano un complesso rituale assieme alle parentatio che furono spostate al mese di Februarius con la riforma “di Numa”.

Per come ci è nota dalle fonti, la festa dei Saturnalia aveva notevoli rassomiglianze con le Kronia greche (dedicate a Kronos, divinità a cui Saturnus sarà assimilato), fatto dovuto probabilmente ad una riorganizzazione avvenuta nel III sec. aev, benchè queste ultime cadessero in estate, dopo la semina.

È possibile che, in tempi antichi, la festa avesse un carattere agricolo e fosse legata alla chiusura del periodo della semina [Plut. Q. R. 34] e all’arrivo dei giorni più oscuri dell’anno. Per questo motivo forse un tempo fu celebrata fuori dalle mura urbane, sull’Aventino con un carattere rustico (la cittadinanza era invitata a rusticari, festeggiare alla maniera dei contadini) [Porc. Latro In Catilin. XVII].

L’organizzazione della festa, per come la conosciamo dalle fonti storiche, risale al 217 aev dopo la sconfitta del Lago Trasimeno e avvenne in seguito alla consultazione dei Libri Sibillini [Liv. XXII, 1]; è probabilmente a quest’epoca che risale l’influenza delle analoghe feste greche, le Kronia. I festeggiamenti comprendevano un solenne sacrificio al tempio di Saturnus, seguito dal banchetto sacrificale pubblico [Dion. H. VI, 1], un lectisternio compiuto dai senatori, in cui era portata in processione anche la statua del Dio che si trovava all’interno del tempio ed era avvolta da bende di lana [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 5; Plut. Q. R. 61; Lucian. Kron. X; Saturn. VII; De Saltat. XXXVII] e pubblici banchetti [Liv. Cit.]; la popolazione si riversava nelle vie gridando

Io Saturnalia, bona Saturnalia [Mart. XI, 2, 5; XIV, 70; Arr. Epic. Dissert. IV, 1, 58; Cat. XIV, 15; Liv. XXII, 1; Petr. Sat. LVIII; Macrr. Sat. I, 10, 18]

e i festeggiamenti duravano giorno e notte senza interruzione [Tert. Apol. 42].

Per tutto la durata dei Satunalia non si lavorava, nè si svolgeva l’attività giudiziaria, nè si poteva combattere [Mart. VIII, 84, 1; Plin. Ep. VIII, 7, 1; Suet. Aug. XXXII; Macr. Sat. I, 10, 1]. Venivano concesse amnistie e i condannati così liberati votavano le proprie catene a Saturnus. Era il periodo preferito per affrancare gli schiavi ed essi offrivano al Dio i proprii anelli di bronzo [Mart. V, 85, 1; Lucian. Saturn. XIII; Macr. Sat. I, 10, 16]. In età imperiale si svolgevano anche combattimenti di gladiatori [Auson. De Feriis XXXIII; Lact. Inst. VI, 20, 35]

Questo periodo era caratterizzato da grande allegria, rilassatezza e licenziosità [Gel. XVI, 7, 11; Macr. Sat. I, 10]; avveniva anche una sorta di annullamento delle distinzioni sociali, in omaggio all’Età dell’Oro di Saturnus in cui non vi erano padroni e servi: era prassi vestire in modo comodo, indossando solo la synthesis (tunica) e non la toga [Mart. IV, 24; V, 79; XIV, 1; XIV, 141; Macr. Sat. I, 1], inoltre tutti portavano il pileum [Mart. VI, 3; VIII, 4; XIV, 1, 2], il copricapo degli schiavi affrancati, che aveva un più ampio significato di liberazione, e gli schiavi erano trattati al pari dei padroni [Macr. Sat. I, 24, 23; Just. XLIII, 1, 3; Accius FPR III, pg 267 apud Macr. Sat. I, 7, 37]. Si arrivava perfino ad un vero e proprio rovesciamento dei ruoli e i padroni servivano a tavola i loro servitori, così come accadeva ai Matronalia (vedi Kal. Mart.) [Macr. Sat. I, 12, 7], e questi ultimi si potevano permettere una libertà di linguaggio che altrimenti non sarebbe stata consentita [Hor. Sat. II, 7, 4]. Agli schiavi era anche consentito il gioco d’azzardo, che nel resto dell’anno era loro vietato [Mart. V, 30, 8; Macr. Sat. I, 6, 13; I, 7, 20 – 37; Arr. Epict. Dissert. IV, 1, 58; Sen. Apokol. VIII] Per questo la festa era chiamata anche Feriae Servorum.

La festa si svolgeva anche fuori Roma e i soldati celebravano i Saturnalia nelle province così come in patria [Cas. Dio. LX, 19].

In privato si libava vino e si sacrificava un piccolo porco al Genius individuale e a Saturnus [Hor. Car. III, 17, 14; Dion. H. VI, 1; Mart. XIV, 70; Lucian. Sat. XIV] e si offrivano prodotti agricoli: formaggio, cereali, liba [Fest. 86]. Il sacrificio a Saturnus si svolgeva graeco ritu, con il capo scoperto [Fest. 119; 322; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 2; Dion. H. I, 34; VI, 1; Serv. Aen. III, 407; Plut. Q. R. 11].

… graeco ritu Saturnali fiebantur… [Cato. ORF pg 65 Meyer apud Priscianus]

Nelle case si celebravano convivi a cui erano invitati amici e conoscenti e ci si scambiava regali [Mart. IV, 46, 88; V, 18; VII, 53; VIII, 41; X, 17; XI, 6; XIV, 1, 9; ecc…; Stat. Silv. I, 6, 5; Plin. Nat. Hist. XIII, 3; Sen. Ep. XVIII; Apokol. XII; Suet. Vesp. XIX] chiamati apophoreta, in modo analogo a quanto accadeva ai Matronalia (vedi Kal. Mart.) [Juv. IX, 53; Suet. Vesp. XIX, 1; Digest. 24, 1, 31, 8; Plaut. Miles. 689 – 690]. Marziale riporta alcuni esempi di questi doni

… mezzo moggio di farro e fave macinate, tre mezze libbre d’incenso e di pepe, delle salsicce lucane con trippa alla falisca, una bottiglia siriaca di vin cotto, fichi glassati in un vaso di Libia, cipolle, lumache, formaggio… un panierino che poteva a stento contenere una manciata di olive, un servizio da tavola per sette… una salvietta ornata con un largo bordo di porpora… [Mart. IV, 46; cfr. VII, 53; Stat. Silv. IV, 9]

In età repubblicana si trattava solamente di ceri e bambole di argilla o pasta chiamate sigilla, da cui la festa prese anche il nome di sigillaria. I ceri venivano accesi durante i banchetti ed erano una protezione contro le lunghe notti invernali ed una sorta di appello al ritorno del sole, nel periodo del solstizio invernale [Macr. I, 7, 28 segg; I, XI, 39; Var. L. L. V, 34; Dion. H. I, 10; Fest. 54; Mart. V, 18, 2; Lact. Inst. I, 21, 6]. I sigilla, che erano simili agli oscilla e alle maniae appese sulle porte per proteggere gli abitanti della casa durante i Compitalia, ricordavano i sacrifici umani che un tempo erano computi dai Pelasgi in onore di Saturnus e che furono poi sostituiti dall’offerta dei ceri [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28; I, 10; I, 11, 1; I, 11, 24]. Sigillaria era anche il nome che veniva dato in generale ai regali scambiati durante i Saturnalia [Sen. Ep. XII; Mart. VII, 53; Suet. Claud. V].

Per limitare la diffusione di regali più costosi un tribuno della plebe di nome Publicio (probabilmente nel 209 aev), fece votare una legge che, in occasione dei Saturnalia, obbligava tutti a scambiarsi solo i tradizionali ceri e sigilla [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28]; tuttavia sappiamo che in età imperiale la natura dei doni era cambiata: Marziale, infatti, dedicò i libri XIII e XIV dei proprii epigrammi (intitolati rispettivamente Xenia e Apophoreta) proprio a questi regali: non vi compaiono più ceri e sigilla, ma oggetti di poco valore, cibi, incensi e altre sostanze odorose, mobili, oggetti di lusso, gioielli, abiti, libri, utensili e altri oggetti utili, come le lanterne e schiavi. Spesso i regali divenivano premio di lotterie e giochi d’azzardo [Mart. IV, 14, 7; XI, 6; XIV, 1, 4; Tac. Ann. XIII, 15; Arr. Epict. Dissert. I, 25; Lucian. Saturn. III, 4; Macr. Sat. I, 5, 7 – 11]; i poveri e gli schiavi scommettevano delle noci che divennero un altro simbolo della festa, saturnaliciae nuces [Mart. V, 84, 9; XIV, 1, 3].

Anche gl’imperatori partecipavano a questi scambi di doni, sono famosi quelli di Augusto, assegnati tramite una lotteria [Suet. Aug. LXXV] che comprendevano beni di lusso, oggetti esotici, antichità, denaro e metalli preziosi [Suet. Aug. LXXI; LXXV; Stat. Silv. I, 6; Lucian. Cronosol. XIV – XVI]. Era anche usanza donare una Saturnalicia sportula [Gir. Ad Ephes. VI, 4].

Saturno in Foro

The temple of Saturn was built near an ancient altar in a corner of the Forum at the foot of the Capitol [in faucibus (Capitolii) Var. L. L. V, 42; in the Roman Forum Liv. XLI, 21, 12; Forum for Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1; in imo clivo Capitoline Fest. 322; Serv. Aen. VIII, 319; sub clivo Capitoline OGR. III, 6; ante clivum Capitolinum Serv. Aen. II, 116, Hygin. Fab. 261; Dion. H. I, 34, 4; VI, 1, 4]. It was the oldest temple mentioned in the archives of the pontefices; a tradition ascribes its construction to Tullo Hostilius, while according to another was begun by the last Tarquin [Var. apud Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1; Dion. H. VI, 1, 4] and then dedicated at the beginning of the Republic by Titus Larcius, dictator in 500 BCE [Macr. cit.], or from Aulus Sempronius and M. Mamercus, consuls in 497 BCE. [Liv. II, 21; Dion. H. Cit.], or by Posthumus Cominius, consul in 501 and 493 BCE. [Dion. H. Cit.]; another version wants it to be built by Titus Larcius during its second consulate in 498 BCE. [Dion. H. VI, 1, 4]. A different tradition, transmitted by Gellius, attributes it to L. Furio, military tribune, in execution of a decree of the Senate [Gel. apud Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1]. In any case, the temple can be traced definitely the beginning of the republican period. In 174 BCE a porch along the ridge of the Capitol, the temple of Saturn, to the top of the hill was built [Liv. XLI, 27, 7]. In 42 BCE it was rebuilt by L. Munatius Plancus [Suet. Aug. 29; CIL VI, 1316; X, 6087]. In the fourth century it was damaged by fire and restored by a Senate vote [CIL VI, 937]. The date of the dedication was the 17th to Dec. Saturnalia [Fast. Amit. XVI to Kal. Jan., CIL I2, 245; 337; Liv. XXII, 1, 19].

During the Republic, the temple housed the state treasury, the aerarium populi Romani or Saturns, in charge to quaestors [Fest. 2; Solin. I, 12; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 3; Plut. Tib. Grac. X; App. B.C. I, 31]; there was a balance that was once used for payments and which remained as a symbol of this function [Var. L. L. V, 183]. During the Empire it maintained this function, but the aerarium Saturns was only the part of public funds under the control of the Senate, distinguished from the fiscus emperor, administered by praefecti instead quaestores [Plin. Ep. X, 3, 1; The S. ling. Lat. I, 1055 – 1058]. The offices of public officials were probably outside, in the Saturnian until the construction of the Tabularium in 78 BCE. when they were transferred to the archives. Other public documents were posted on the walls of the temple and its columns [Cass. Dio XLV, 17, 3; CIL Ia, 587, col. 2, 1, 40; Var. L. L. V, 42).

In the tympanum were statues of Tritons and horses [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 4], and the cell was a statue of Saturnus that was oiled and wrapped in woolen blankets [Plin. Nat. Hist. XV, 32; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 5; Rosch. IV, 431] and carried in solemn processions [Dion. H. VII, 72, 13].

Saturnalia

The Saturnalia was the feast dedicated to Saturnus. Originally they lasted only one day, but popular usage extended them up to seven days [Macr. Sat. I, 10, 1-5; 18 – 24; CIC. to Att. XIII, 52], so as to comprise Opalia and Larentalia. This expansion was probably favored, at the beginning, by the identification of Saturnus and Ops with Kronos and Rhea, and therefore with the desire to join the festivities dedicated to these two gods. Augustus added just three days, which were later increased to five [CIL I, 337] and, later, again to seven; however, only the days when religious festivals were falling festi [Macr. Sat. I, 10, 24].

Wide digression on the possible origins of this festival lies in the Saturnalia of Macrobius [Macr. Sat. I, 7]. In an era extremely ancient Lazio ruled on Janus, with His bride Camesis; their capital was in Mount Janiculus. Saturnus, arrived on board a ship, settled there and inaugurated the practice of agriculture (the epithet Stercutus means that He was the first to fertilize fields), the cultivation of fruit trees, the graft and processing of foods, which is the reason because His statue holds a sickle; He built His city, Saturnia, on the mountain that was once called Saturninus and then Capitol [Var. L. L. V, 42; Dion. H. I, 34; Fest. 322; Solin. I, 13; Serv. Aen. II, 115; Verg. Aen. VIII, 321]. In honor of Saturnus arrival, the first Roman coins had the prow of a ship and the image of God. After a long reign Saturnus disappeared and the Janus bestowed a cult, building an altar (ara Saturnian or fanum Saturnian in faucibus at the foot of the Capitol [Var. LL V, 42; Dion. H., 34]), and held the first Saturnalia. The kingdom of Saturnus was a golden age: there was no distinction between slaves and free men, and there was plenty of food and wealth. His cult would then be brought forward by comrades who left Hercules in Italy during its passage and who settled on Mount Saturnius [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 18 – 27].

Another version traces the origin of Saturnus worship to the Pelasgians: the oracle of Dodona prescribed them, when you get to Lake Cotila and defeated the Aborigines, to consecrate the tenth of the spoils to Apollo, to sacrifice the heads to Ades and men in Saturnus – Kronos. They followed his instructions and, once settled in Italy, built a temple to Hades and an altar for Saturnus, where accomplished right sacrifices; they also created the first festival in honor of Saturnus [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28-31]. When Hercules arrived in Italy, He puts an end to human sacrifice and it convinced the people to offer to Ades simulacra shaped heads (swings) and Saturnus of lighted candles instead of humans [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 31-32]. Both versions trace the cult of Saturnus to a much earlier period the foundation of Rome.

In a further version of the founding of Saturnalia was concomitant to the dedication of the temple of Saturnus, accomplished by Tullo Hostilius, or by Tarquinius Superbus or by a military tribune by order of the Senate [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 1].

The Saturnalia, along with Divalia and Larentalia, are part of a system of festivities dedicated to the chthonic deities (Saturnus was considered chthonic God [Plut. QR 11; 34] or inferior [Mart. Chap. I, 58]) at the end of the ancient Roman calendar, which probably formed a complex ritual along with parentatio that were moved to the month of Februarius with the reform “Numa”.

It is possible that, in ancient times, the party had an agricultural character and was linked to the end of the period of sowing [Plut. QR 34] and the arrival of the darkest days of the year. For this reason perhaps was once celebrated outside the city walls, on the Aventine with a rustic character (citizenship was invited to rusticari, celebrate the way the peasants) [Porc. Latro in Catilin. XVII].

The festival organization, as we know from historical sources, dates back to 217 BCE after the defeat of the Trasimeno Lake and took place following consultation of the Sibylline Books [Liv. XXII, 1]; It is probably at this time that goes back the influence of similar Greek celebrations, the Kronia. The festivities included a solemn sacrifice in the Temple of Saturnus, followed by the public sacrificial banquet [Dion. H. VI, 1], a lectisternium made by senators, which carried in procession the statue of the God who was inside the temple and wrapped in bandages of wool [Macr. Sat. I, 8, 5; Plut. Q. R. 61; Lucian. Kron. X; Saturn. VII; De Saltat. XXXVII]; there were public banquets [Liv. Cit.] and people poured through the streets shouting

I Saturnalia, bona Saturnalia [Mart. XI, 2, 5; XIV, 70; Arr. Epic. Dissert. IV, 1, 58; Cat. XIV, 15; Liv. XXII, 1; Petr. Sat. LVIII; Macrr. Sat. I, 10, 18]

The celebrations lasted day and night without interruption [Tert. Apol. 42].

Throughout the duration of Satunalia not working, nor was held up legal proceedings, nor could fight [Mart. VIII, 84, 1; Plin. Ep. VIII, 7, 1; Suet. Aug. XXXII; Macr. Sat. I, 10, 1]. Amnesties were granted and convicts released so they voted their chains to Saturnus. He was preferred to free the slaves and they offered to God their bronze rings [Mart. V, 85, 1; Lucian. Saturn. XIII; Macr. Sat. I, 10, 16]. In imperial there were also gladiator fights [Auson. De Feriis XXXIII; Lact. Inst. VI, 20, 35]

This period was characterized by great joy, relaxation and licentiousness [Gel. XVI, 7, 11; Macr. Sat. I, 10]; a kind of cancellation of social distinctions occurred, in homage to the Golden Age of Saturnus where there were masters and servants, it was practice to dress comfortably, wearing only the synthesis (tunic) and not the toga [Mart. IV, 24; V, 79; XIV, 1; XIV, 141; Macr. Sat. I, 1], all wore Pileum [Mart. VI, 3; VIII, 4; XIV, 1, 2], the headgear of freed slaves, who had a broader meaning of liberation, and the slaves were treated in the same masters [Macr. Sat. I, 24, 23; Just. XLIII, 1, 3; Accius FPR III, pg 267 apud Macr. Sat. I, 7, 37]. Even happened a real role reversal and the bosses served at the table his servants, as at Matronalia [Macr. Sat. I, 12, 7], and the latter could afford a freedom of speech that otherwise would not have been allowed [Hor. Sat. II, 7, 4]. Slaves were allowed gambling, while in the rest of the year they were forbidden [Mart. V, 30, 8; MACR. Sat. I, 6, 13; I, 7, 20-37; Arr. EPICT. Dissert. IV, 1, 58; Sen. Apokol. VIII]. For this reason the festival was also called Feriae Servorum.

It was held also outside Rome and soldiers celebrated the Saturnalia in the provinces as well as at home [Cas. Dio. LX, 19].

In private libation with wine were poured and a small pig to the Genius and Saturnus was sacrificed [Hor. Car. III, 17, 14; Dion. H. VI, 1; Mart. XIV, 70; Lucian. Sat. XIV], people offered agricultural products: cheese, cereals, liba [Fest. 86]. The sacrifice took place graeco ritu, with bare head [Fest. 119; 322; Macr. Sat. I, 8, 2; Dion. H. I, 34; VI, 1; Serv. Aen. III, 407; Plut. Q. R. 11].

… Graeco ritu Saturnalia fiebantur … [Cato. ORF pg 65 Meyer apud Priscianus]

Feasts were celebrated in the homes to which peoples invited friends and acquaintances and there were gifts exchange [Mart. IV, 46, 88; V, 18; VII, 53; VIII, 41; X, 17; XI, 6; XIV, 1, 9; etc …; Stat. Silv. I, 6, 5; Plin. Nat. Hist. XIII, 3; Sen. Ep. XVIII; Apokol. XII; Suet. Vesp. XIX] called apophoreta, in a way similar Matronalia (see Kal. Mart.) [Juv. IX, 53; Suet. Vesp. XIX, 1; Digest. 24, 1, 31, 8; Plaut. Miles. 689-690]. Martial lists examples of these gifts

… Half a bushel of barley and broad beans ground, three half pounds of incense and pepper, sausage with tripe falisca Lucan, a bottle of Syriac cooked wine, glazed figs in a pot of Libya, onions, snails, cheese … a little basket who could barely contain a handful of olives, a table service for seven … a towel adorned with a wide border of purple … [Mart. IV, 46; see. VII, 53; Stat. Silv. IV, 9]

In Republican era they were only candles and clay dolls called sigilla, so the festival took also the name of Sigillaria. The candles were lit during banquets and they were a protection against the long winter nights and a kind of appeal to the return of the sun, in the period of the winter solstice [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28 segg; I, XI, 39; Var. L. L. V, 34; Dion. H. I, 10; Fest. 54; Mart. V, 18, 2; Lact. Inst. I, 21, 6]. The seals, which were similar to the swings and maniae hung on the doors to protect the inhabitants of the house during the Compitalia, reminded the human sacrifices that were once calculations by the Pelasgians in honor of Saturnus and which were later replaced by the offer of the candles [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28; I, 10; I, 11, 1; I, 11, 24]. Sigilla was also the name given to gifts exchanged during the Saturnalia [Sen. Ep. XII; Mart. VII, 53; Suet. Claud. V].

To limit the spread of more expensive gifts a tribune of the people named Publicius (probably in 209 BCE), had to pass a law that, during the Saturnalia, forced everyone to exchange only the traditional candles and seals [Macr. Sat. I, 7, 28]; yet we know that in imperial period, the nature of the gifts had changed: Martial, dedicated books XIII and XIV of his epigrams (entitled respectively Xenia and Apophoreta) precisely to these gifts: there appear more candles and seals, but objects of little value, food, incense and other perfumes, furniture, luxury items, jewelry, clothing, books, tools and other useful items such as lanterns and slaves. Often gifts became award of lotteries and games of chance [Mart. IV, 14, 7; XI, 6; XIV, 1, 4; Tac. Ann. XIII, 15; Arr. EPICT. Dissert. I, 25; Lucian. Saturn. III, 4; Macr. Sat. I, 5, 7-11]; the poor and the slaves were betting the nuts that became another symbol of the holiday, saturnaliciae nuces [Mart. V, 84, 9; XIV, 1, 3].

Even emperors took part in these exchanges of gifts, are famous those of Augustus, assigned through a lottery [Suet. Aug. LXXV] that included luxury goods, exotic items, antiques, money and precious metals [Suet. Aug. LXXI; LXXV; Stat. Silv. I, 6; Lucian. Cronosol. XIV – XVI]. It was also customary to give a Saturnalicia Sportul [Gir. Ad Ephes. VI, 4].

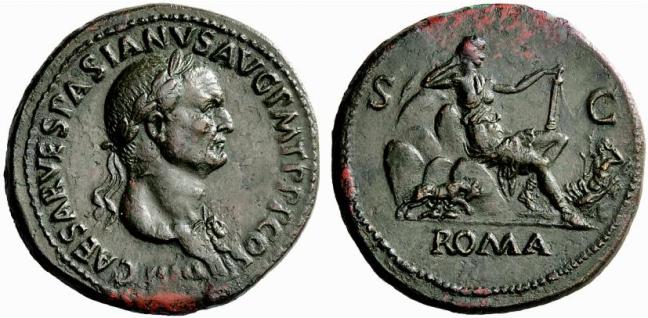

Picture: Saturn fresco from Pompei